AMBA AXI and OCP: Behind the Standards

, 2011年04月04日

First some history: In 2003, ARM launched AMBA 3, which included the Advanced eXtensible Interface (AXI) while in

2001 the Open Core Protocol (OCP-IP) organization started work on what became the OCP specification. In both

cases, these standards purportedly decoupled the interface choice from the interconnect topology, which was an

improvement over traditional busses.

They were both meant to solve pretty much the same problem. The idea was that these new

They were both meant to solve pretty much the same problem. The idea was that these new

protocols would be able to connect more complicated IP blocks together and surpass some of the limitations of

the older AHB and internal/proprietary protocols. It was hoped that these protocols would be immediately adopted

by many of the large companies that already had their own internal protocols.

Looking under the covers there also were other reasons for creating these protocols. In the case of AXI, it was

an economic complement to ARM’s core CPU IP product, just as buns are a complementary product to hamburgers. ARM

provided the AXI standard because it wanted to make it easier to connect its AXI-based CPU cores to other IP,

and it of course helped if the IP spoke the same language as the CPU socket. The architecture of the cores drove

the requirements for the socket protocol. This made life easier for SoC developers using only AMBA protocol IP,

but caused complications for customers who had their own protocols or who wanted to use IP from a vendor who was

not using AMBA.

In a similar vein, when OCP came out it was meant to address the issue of not having an industry-standard

protocol that could be used by any type of CPU or DSP core, and wasn’t driven by a single IP vendor. However,

one of the issues with the adoption of OCP was that there was only one fabric IP vendor supporting it at its

inception and only one topology option, a shared bus fabric IP.

From an engineering standpoint, we would all love to have one lingua franca used by all IP vendors to speak the

same language at the transaction level. This would make it very easy to integrate plug-and-play IP and totally

decouple interconnect fabric topology choices from the choice of protocol. But organizations that promulgated

sockets and transaction protocols had an economic interest in increasing the switching costs from their IP, in

effect making it “sticky” and “locking in” customers. In classical economics this cost of switching from one

choice to another includes the opportunity cost of what the customer could do if they made the switch. The total

switching cost is borne by the customer.

We see the economics of this every day. Think of the triple-play bundling we have with our cable TV, phone and

Internet. Sure, you get a little lower price. But that price doesn’t account for the cost and pain you will have

if you decide switch to a new vendor after you make the initial choice. The point of bundling is to create

switching costs, not to offer you a better price. (By the way, do we ever see bundling in the IP market?)

But there’s also a hidden IP protocol cost manifested within the SoC, adversely affecting features, schedules and

cost. How many times have you seen the topology of an interconnect being affected by the transaction protocol

being used? How many times have we seen bridges and additional bus layers inserted to accommodate mixed

protocols?

There has to be a better way within the SoC of limiting IP switching costs and separating the choice of

transaction protocol from the topology of the interconnect fabric. And there is.

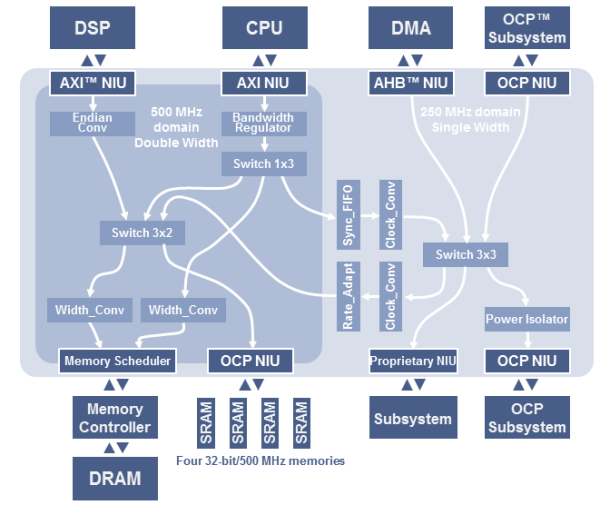

The solution is to encapsulate the transaction protocol into the transport protocol at the very edges of the

interconnect fabric. Therefore, the interconnect can be 100% agnostic as to the CPU sockets and IP transaction

protocols and can be driven by system requirements. Communication within the SoC system can be driven by the

needs of the chip rather than the needs of a particular IP block on the chip.

A big economic benefit of doing this is that it reduces the switching costs of the intended or unintentional

lock-in of IP transaction protocols. In other words, it makes it very simple to plug-and-play the best IP to

meet the requirements in the best way for the SoC designer and their customers. The end result is a huge

reduction of IP switching costs, increased flexibility for the SoC designer and a better performing chip because

the interconnect topology is 100% decoupled from IP choices and is based on the requirements of the overall

system.

a Creative Commons Attribution license.